BIG GAMELAN RANT

joined my first gamelan ensemble last night. had a bajillion thoughts. it's virgo season!

last night i joined this fall’s first rehearsal of gamelan kusuma laras, a javanese gamelan ensemble based inside the consulate general of the republic of indonesia. a lot of things triggered this interest, but it’s a long story…

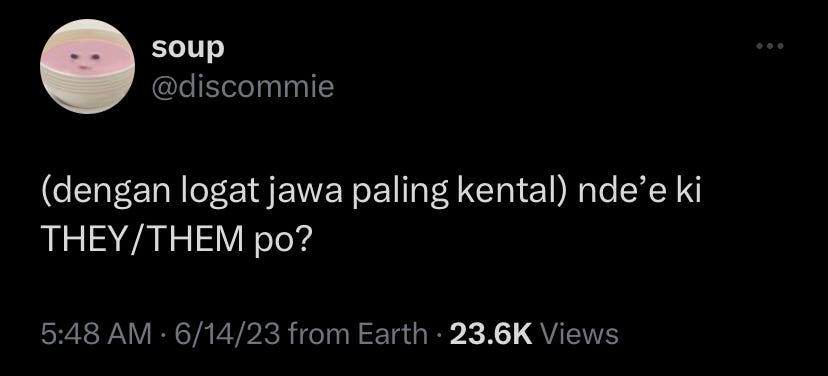

in terms of familial connections, i am as javanese as they get. my dad grew up in semarang with relatives in magelang, and an ancestry that roots to solo - all in central java. and even though my mom grew up in bogor, west java, my grandfather from my mom’s side is from jogjakarta, central java, with an ancestry rooting from that city. i myself was born and raised in the suburbs of jakarta, with very few javanese people around me outside of my family. maybe that’s why i’ve always considered myself a fake javanese - i can’t really speak a word of javanese except for some javanese-isms (saying “sik” when i want someone to wait for me, “moh” when i refuse something, “uwis” when something is done, etc). i also come from a upper-middle class upbringing, with an education emphasis on international modes and english language-based culture, which disconnected me from learning about my own culture, or stopped me from seeking it out.

when i moved to the united states, there is a responsibility that i didn’t have to carry when i was in indonesia: the burden of representation. moving to the united states means oftentimes i could be the only indonesian in the room, and the only indonesian some americans know. i then become the center of information about indonesian culture, therefore i need to represent indonesia in signifiers of culture. which is a big task to do. this is why a lot of international students in the united states (who are often also upper-middle class) often resort to simplistic identifiers that westerners mostly understand, such as gamelan, wayang, rendang, nasi goreng, batik… i find this problematic, and it’s related to the gargantuan task of collapsing a nation as complicated as indonesia to a single representative culture… which i will explain later.

fast forward to last year. i was fresh off a 2.5 year relationship, and back in the dating scene. i started casually seeing a white american - for our first date we went to a hardcore punk fest then got pierogis after. we bonded through our interest in experimental music … and three dates in he dropped something - he mentioned that he is part of a gamelan ensemble and he has done tours across java playing gamelan. i was a little taken aback because it’s very rare that i find an american this immersed not only to indonesian culture, but to javanese culture. we ended up comparing experiences on javanese music throughout the night.

after that date, i thought about how little i know about indonesia. i felt a little insecure because someone who has no connection to indonesia knows about this part of indonesia more than i do. i called my mom, talked to my friends, texted my aunt (who is part of the community gamelan ensemble in wesleyan, one of the biggest gamelan programs in the united states) and came to the conclusion that… is gamelan really my culture? again more on this later.

this year i decided to bite the bullet and join gamelan kusuma laras. here’s some of my observations.

(i got no picture related to gamelan, so this was a gamelan set from someone with the same name as my last name i spotted in jogjakarta)

part 1: the music

the first thing i notice about gamelan is IT IS SO EASY!!!!! it’s literally just banging mallets on a set of metal. i played the vibraphone in marching band, which is also banging mallets on a set of metal, but sometimes i have to do four mallets in two hands which makes it way harder. the only tricky part in gamelan is dampening - you need to silence the piece of metal when you hit the next note, so it doesn’t create a reverb. but i’ve played four mallets in two hands before, so this was an easier challenge for me.

what i realized was that gamelan works like any other music ensembles. you need to have a sense of rhythm and you need to LISTEN. listen to the main tempo by listening to the kendhang player, listen when to come in from the gong and the bonang, listen around you to sync up together. my aunt sometimes complains about how her group sucks because a lot of the members of her community gamelan does not understand tempo nor they listen to each other. but it comes natural for my aunt - my mom’s side of the family grew up pretty musical and my grandmother & aunt is part of a few choirs. i’m also experienced in ensemble groups - marching band, rock band, classical guitar ensemble, angklung, choir, church pop ensemble, etc… all in grade school…

my friend lerry has been emphasizing to me all these years about how i’m no less indonesian despite not knowing a significant chunk of javanese culture, and how these white americans who study gamelan will never be indonesian. i’ve believed that in theory, but this is the first time i actually believe it in practice, because gamelan is sooooo damn easy. at least from the instruments i tried the first time - saron, demung, slenthem, gender.

which takes us to…

(tugu jogja monument in the middle of jogjakarta, taken through my parents’ car in 2019)

part 2: the culture

my conclusion from last year’s conversations with my family and friends is that … my javanese family is as much of a stranger to gamelan than americans. sure we have it incorporated in javanese culture - it’s music used in weddings, birthdays, ceremonies, etc, but it’s not necessarily day-to-day music that we listen to on the regular. we only know how calming the tunes make us feel, or how it fits the context of whatever it is being performed with - javanese dances or wayang performances. i believe the only people in java who listens to it on the reg is only if you’re sultanate royalty.

my extended family are mostly working class folks throughout central java. sure, i have jogja and solo sultanate ancestry from both my parents’ side, but both of them let go of their royalty to marry commoners. the kind of javanese culture i am more acquainted to is stuff that is more considered lowbrow culture: campursari, dangdut, lakon, print batik made into daster, post-processed foods like jadah tempe or tempe gembus, compared to javanese highbrow culture: wayang, gamelan, very fine painted batik that cannot be cut, dutch-indonesian cuisine. none of these culture are better or more real than the other, all of it influenced by the sociopolitical context surrounding it.

as it stands, then, there are two javas: the upper class sultanate-tied culture, and the working class commoner culture. and you might argue there’s multiple layers of this javanese experience - javanese culture distorts as it travels through significance, especially noting that javacentrism is extremely pervasive in indonesia, and how the javanese are the most influential people in indonesia (i’d consider us the white people of indonesia). the way we cut tumpeng, for example, has been distorted through western influences as it is brought to state ceremonial purposes by the oligarchy. and because of javacentrism, the most obvious elements of javanese culture like wayang, gamelan, and batik becomes to forefront of the tools of representation we use to explain our indonesian-ness to americans.

so it’s fair to ask: was there ever a unified javanese culture? and in a broader definition, is there a unified indonesian culture? the question of indonesia as a nation has been brought up by scholars (and together with the concept of nationalism - benedict anderson has a 200-page explanation of that in imagined communities) but i’d like to propose a hypothesis.

no, there is no such thing as a unified indonesian culture. what makes us indonesian is not the shared culture, but the shared pain.

i was born in the death throes of the soeharto dictatorship, on june 1998, in a hospital in the kuningan neighborhood of jakarta. the exact same neighborhood that saw its share of burned tires and protestors’ blood a month prior. growing up there’s always this looming existential knowledge of how our nation came to be, from 300 years of dutch colonialism, to the still taboo topic of the 1965-66 genocide. and how even after the fall of the new order things remain the same, and we are so used to oligarchy, government incompetence, and natural disasters. so we laugh it off! we meme it to death, or we remain nonchalant about it. indonesians are the chillest people in the world, and because we have ingrained so much of our shared pain, so it becomes normal to us. my friend lerry has a wonderful film summarizing this experience, in the context of the shared pain of suicide bombings and islamic extremism in the 2000s.

i have friends from other parts of indonesia that i can connect through this pain, even though i have no bearing of their cultural situation. for example, i might not understand the culture or customs of my friend juan from manado, but we can talk for hours about our government’s incompetence.

and that brings us to the next topic…

(some friends and i at the 2024 nyc indonesian street fair)

part 3: the question of cultural appropriation

being in that gamelan rehearsal session and knowing about the shared pain of being indonesian made me think more on the question of cultural appropriation. i’ve noticed from my indonesian american friends that they are less lenient about cultural appropriation compared to me. they might be more irked about white people playing gamelan, for example. i also observe this in a lot of diaspora-FOB cultures - like when ghost in the shell came out with scarlett johansson starring, a lot of asian american diaspora are more strict about cultural appropriation compared to japanese folks in japan, who mostly think it’s fine.

this definitely has ties to the relationship between the oppressed and the oppressor at a current situation. i once talked about this with my friend dylan from mauritius, who, if they were to date a white person, would feel weird if his partner learns mauritian creole. i understand where he comes from, and sometimes i feel the same way with white people, but it holds less weight in my experience than dylan’s experience. dutch colonization may still have ramifications to our current indonesian society, but it does not have the same impact as, for example, african and west indian countries occupied by france. dutch colonization felt so long ago and, in our current climate, oligarchs and political dynasties are more of oppressive forces than white people. our anger is more directed to them, who are actively restricting our rights, compared to random white people. if i were to date an oligarch like kaesang pangarep (in which i would kill myself first before having to do that to myself), i’d be very, very uncomfortable if i were to have a date with him at a warmindo.

thinking back about white people who play gamelan, now that i’ve learned how to play, it feels like learning gamelan is just an entry level cultural introduction to indonesia for these white folks who have the resources to do so. i mean… it’s just banging pieces of metal with a mallet!!! you just need 5 minutes of tutorial, some sheet music, and a good understanding of rhythm and coordination with other musicians, and you’re good to go. everyone can play gamelan. there’s no need to be insecure.

the question still remains… what differs appreciation and appropriation? i’m trying to think of things i feel icky about interacting with white americans with an interest in indonesia. i’ve described an experience at length in this post about arizal in new york - especially meeting a white american who collects VHS copies of new order-era indonesian films without understanding the cultural context behind it. there’s a difference between a white american who plays gamelan, which i don’t have a clear lineage of memory of it, while with this guy, i know for a fact that my mom’s generation all grew up watching barry prima movies on the layar tancap, and there is an emotional cost on not being able to watch these movies anymore or not knowing where to seek them out. there’s a LOT of the javanese population who will live and die without knowing how to play gamelan (and it’s all fine) - but the aesthetic and political correlation of new order-era movies are ingrained in the DNA of the people who live in it, and it is insulting to see it stripped from the context of what i grew up with.

which is the same case for my ex, who only knew about indonesia due to the 1965-66 genocide, and would only focus on conversations regarding the west wreaking havoc to indonesian politics. he viewed it in such a scholarly way too, as a western leftist. yes, indonesians are indonesians because of our pain, but that doesn’t mean we should only be defined by our pain. it just feels fetishizing.

so i guess that’s my answer!

part 4: opacity

i had an interesting conversation with mbak nana, one of the facilitators of the gamelan group. she is trying to explain to one of the members the difference that she has seen between western gamelan players and javanese gamelan players. western gamelan players are very technical and skillful, but often lack the rasa gained by javanese gamelan players. together, we were trying to crack where this rasa comes from. it’s a vibe, a feeling, that is gained by the understanding and the immersion of the culture (for example, jogja and solo are WAY slower cities than jakarta or new york), but also from generations of generations of training. javanese gamelan players have closer access to more experienced gamelan masters, and as they imitate their masters, they imitate generations of knowledge.

this all makes sense since i have it in my head for my practice in poetry. my friend in the poetry scene toney advised me once to imitate, and feel the lineage of literature passed down in my work. there’s a few poetry programs out there that leads you to select a specific poet's body of work to learn from. for me, it’s frank o’hara. listening to mbak nana’s conversation, it does flow the same way with gamelan training.

there’s this belief going around in social justice circles where some believe that indigenous people, bipoc, etc are holding guarded information about the world, and that they hold a higher ground in terms of information about culture. which i think is a racist point of view. it brings to mind the stereotype of the noble savage, or the “divine feminine” (see here for a great argument against it from ursula k le guin). i had a conversation with my friend hanna about a post from bisan owda from gaza a few days ago, referencing how she is skeptical about vaccines administered in this genocide. bisan has all right to be skeptical; she shared a post that borderlines with an antivax conspiracy theory, but if you’ve been bombed for 11 months by a genocidal state, wouldn’t you be skeptical too? the problem is people are looking up to the words of bisan as if she’s god, as if she’s the sole representative of palestinians, instead of the experiences of a girl going through genocide. anne frank goes on instagram; we have to remember where she’s coming from.

and it’s the same thing about gamelan. people who learn about indonesian culture needs to understand indonesian pain as well, in a way that doesn’t put us in the noble savage territory. part of demystifying gamelan is to actually learn that it’s just banging mallets to pieces of metal. but at the same time, it’s more than just banging mallets to pieces of metal. you don’t have to understand it now. you don’t have to understand it at all!

part 5: love

mbak nana led the session together with her husband, a white american man. while her husband led the gamelan parts mbak nana would dance or sinden, and sometimes he would sing along with her, supporting her when she would forget parts or lose track.

i walked home and listened to boygenius’s “true blue.” same and same again, the lyrics that hit me the most are “and it feels good to be known so well / i can’t hide from you like i hide from myself.”

when i’m dating someone, or when i’m friends with someone who is not indonesian, i want to be understood in all my indonesian-ness. not just the culture, not just the pain, but the full indonesian experience - how we respond to the changing culture. how we survive the pain.

i once had a fling with someone who doesn’t know anything about indonesia or indonesian culture, but seems to know the most miniscule, random details about indonesia. “don’t you guys chew betel nut?” “don’t you guys have those monkeys who dance on the side of the street” “i think you guys have that nazi rock musician” “you guys sure are very good at nepotism huh” i don’t know where he knows about these things. but i felt more known by this guy than by my ex, who only sees my indonesian-ness through my pain, and refused to learn indonesian or to learn to speak my last name until one year in.

i felt the same thing during the rehearsal. i felt like i wanted to throw all delineation of cultural appreciation vs appropriation out the window. fuck all that! if you want to know me and love me, you have to support me like that - knowing my culture deeper than just surface level fascination, and knowing my pain deeper than just a scholarly endeavor.